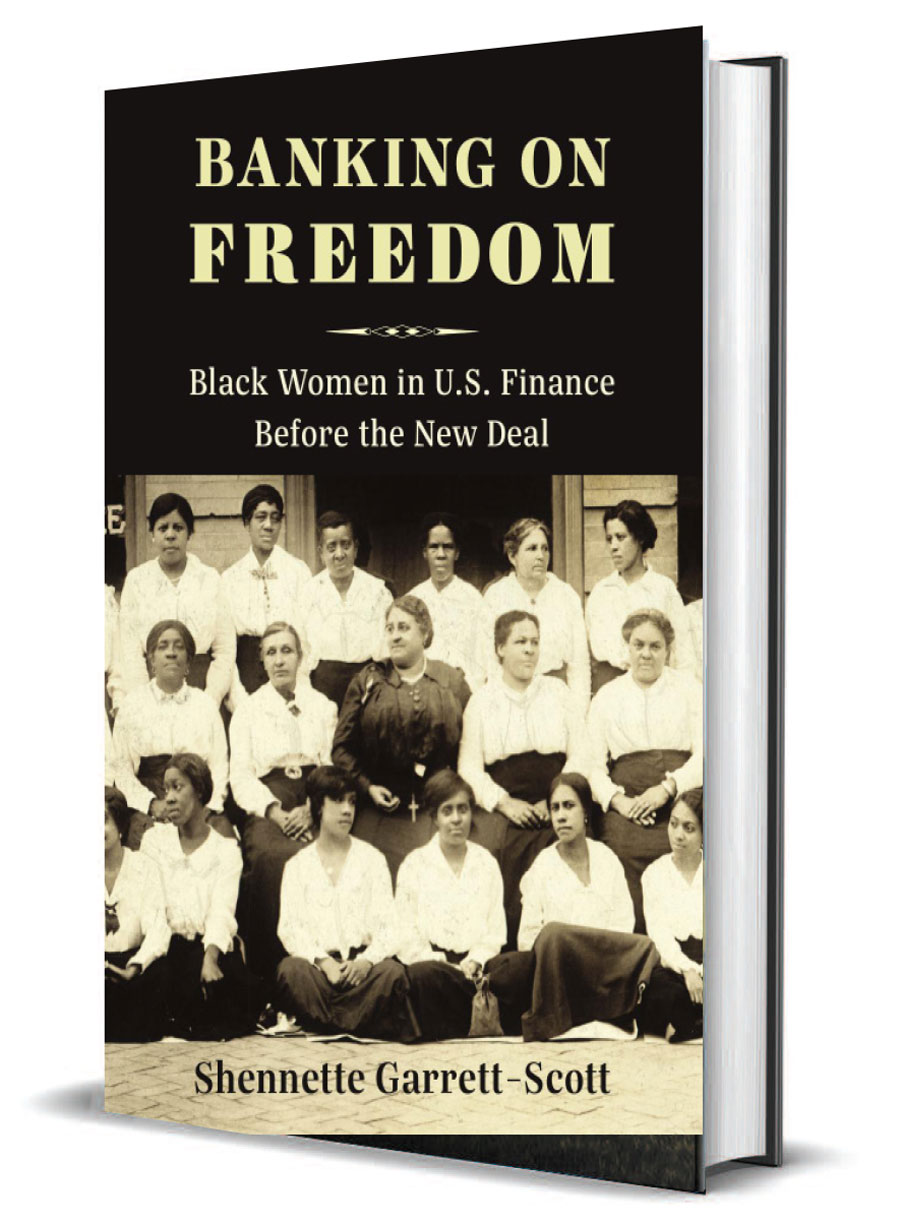

In an October Centennial Virtual Speaker Series lecture, Shennette Garrett-Scott, Ph.D., award-winning author, historian, and professor at the University of Mississippi, discussed her book, Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal.

These are excerpts from her presentation, introduced by Gabelli School Dean Rapaccioli, Ph.D, and David Cowen, Ph.D., president and CEO of the Museum of American Finance, about how Black women recognized the power of investment to create opportunities for employment and housing and to shape the broader meaning of wealth, risk, and opportunity.

DR: What kinds of challenges did Black women face in 1920s New York?

SGS: They confronted limited employment opportunities, squalid housing conditions, skyrocketing rents, and overcrowding in segregated sections of the city. They rejected efforts to police their behavior and the way they spent their leisure time, and they were attracted to the promises of investment as a vehicle for civic inclusion and political rights.

In an October Centennial Virtual Speaker Series lecture, Shennette Garrett-Scott, Ph.D., award-winning author, historian, and professor at the University of Mississippi, discussed her book, Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal.

These are excerpts from her presentation, introduced by Gabelli School Dean Rapaccioli, Ph.D, and David Cowen, Ph.D., president and CEO of the Museum of American Finance, about how Black women recognized the power of investment to create opportunities for employment and housing and to shape the broader meaning of wealth, risk, and opportunity.

DR: What kinds of challenges did Black women face in 1920s New York?

SGS: They confronted limited employment opportunities, squalid housing conditions, skyrocketing rents, and overcrowding in segregated sections of the city. They rejected efforts to police their behavior and the way they spent their leisure time, and they were attracted to the promises of investment as a vehicle for civic inclusion and political rights.

DR: How did they use investment as a way to rise above these challenges?

SGS: The Independent Order of St. Luke was a secret society that was founded in the 1850s by a free Black woman for Black women in Richmond, Virginia. In 1899, the Independent Order of St. Luke came under the leadership of the ambitious Maggie Lena Walker.

In 1921, the New York district of St. Luke’s in Harlem was struggling, so 21 members, mostly women, incorporated the St. Luke Finance Corporation and set their sights on real estate investment. One of these investments was St. Luke’s Hall, a combination community center, apartment building, restaurant, and retail store. Located in the heart of Harlem, St. Luke’s Hall became an important center for business, community activities, and entertainment. It provided safe, affordable housing, restaurants, and retail spaces that offered fair prices and a variety of goods and services as well as good-paying, stable jobs—these were important priorities for Black women and Black communities in general.

DR: Can you tell us a little about Maggie Lena Walker?

SGS: Maggie Lena Walker was born enslaved at the end of the Civil War in Richmond, Virginia. She said that she grew up “not with a silver spoon in her mouth but with a wash basket upon her head.” She grew up poor, but her circumstances shaped her economic vision for Black women.

She transformed the Independent Order of St. Luke into one of the most successful and one of the very few largely Black woman–controlled financial institutions in the country. At its peak in the mid-1920s, it boasted 100,000 members in more than 20 states, nearly 200 employees—the majority of them women—and assets equivalent to about $31 million today.

In addition, she opened the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903, which was the first bank to be led by a Black woman and to be largely financed by African American women.

DR: Why did these banks and institutions disappear and how many exist today?

SGS: Before the Great Depression, there were over 100 African American banks that had been formed since 1888, when the first one was chartered in Richmond. These banks were often limited in where they could operate. They focused largely on African Americans who tended to make less money, and they had difficulty accessing credit and the knowledge that other banks were able to get.

Most could not weather the storm of the Great Depression. So about a dozen banks came cobbling out of the Great Depression era. But there was a revival around WWI and in the 1950s. We have a handful of banks that are more than 100 years old that are still in existence today.

DR: How do we build Black wealth today, and what lessons can we learn from the past?

SGS: Reparations is an issue that needs serious consideration. I’m hoping that HR 40 will finally be dealt with in Congress. That bill is to create a commission to study the question of reparations, not just for slavery but also for racial discrimination and inequity. That’s one important step forward in terms of closing the wealth gap and building wealth today.

I also think that embracing Maggie Lena Walker’s vision is a way to build wealth. Listening to the voices of people in communities, in different spaces, in different industries and asking them what they want and need, then crafting programs and tools to help them meet those needs.

We also need to work to dismantle barriers, especially in lending. Those banking and financial institutions that helped to create stark inequalities [and]need to admit their complicity and then have honest conversations about how we can dismantle those narratives and practices.